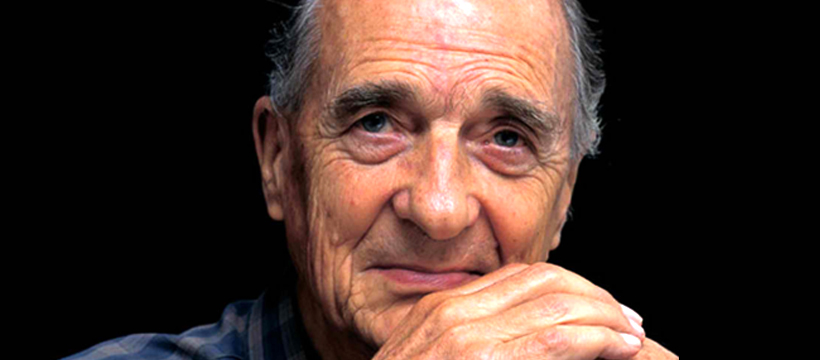

HONOURING CARL NIELSEN 1930–2016

The Industrial Design community in Australia has lost one of its greatest. Carl Nielsen, one of the founding fathers of Industrial Design in Australia has passed away after a long battle with dementia. Carl died peacefully at his home in Bayview with his wife Judy by his side."Carl will always be remembered as one of the first people to establish an Industrial Design Studio in Australia, but more importantly, I will remember him as one of the most kind and gentle people in our industry. He will be greatly missed but his design genius will live on forever. There are so many products still in use today that were touched by Carl's design thinking," said Dr. Brandon Gien, CEO of Good Design Australia.

From the iconic Pedestrian Button, that is still in operation today and sits on every street corner in Australia to the Café Bar, a game changing product in its time, Carl's influence on Australian Industrial Design will never be forgotten.

“Carl has been a great friend and mentor to me for over 30 years. His insights and guidance in both a professional and personal sense have been invaluable. Carl has done more than anyone else I know to raise the profile of Industrial Design in Australia. His ethics in business and passion for design education have contributed to many employed in design today," said Mr. Adam Laws, Managing Director of Nielsen Design.

The iconic PB/5 Pedestrian Button designed by Nielsen Design Associates

The Café Bar “Quintet” by Nielsen Design Associates

Public Transport Commission (NSW) Identity and Signage (1970)

Radiogram (Pye Industries, 1968)

Martin Place Street Furniture, Sydney (1970)

In honour of Carl, Good Design Australia is featuring a selection of historical videos from the early 1960s that were produced by the Industrial Design Council of Australia (IDCA) to promote good design to industry and the general public, featuring Carl and many examples of his work.

Gone but not forgotten, Carl Nielsen 1930-2016

Celebrating 50 Years of Australian Design, 2008

Industrial Design Council of Australia Consumer Education Film Circa, 1965

Australian Industrial Design Training Video, 1967

Inventive Australians, 1988

Tributes to Carl Nielsen can be left HERE

Story from Luminary Archives, Indesign 2014

Industrial design as a profession probably dates from the Bauhaus, established in 1919 as ‘a laboratory for mass consumption’. After World War II, new materials, manufacturing methods and technologies saw the growth of mass production and of industrial design.

But in post-War Australia, industrial design was barely a newborn. Carl Nielsen’s businessman father had been part of a government task force sent to investigate manufacturing overseas. Discovering the developing profession in the United States, he suggested it as a career for the teenage son who liked to spend his time “fixing and making things.” Nielsen had a darkroom set up in the laundry – “I was always interested in photography and made a surprisingly useful income from it” – and a home workshop where he fiddled with cars and motor bikes.

In 1949 he enrolled in the Industrial Design Diploma course at Melbourne Technical College (later RMIT). Industrial design was then firmly married to art and craft and Nielsen wondered where the course, “run by a well-known fine artist and… other ‘arty’ types”, was taking him. “It was a very esoteric thing to do in the 1950s.”

The family moved to Sydney and Nielsen continued to make a living taking photographs at car and motorbike races and portraits of children and their families. He also designed and made furniture, which he sold through interior design outlets. After some invaluable experience as a designer at Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA) and then in the UK for household appliance manufacturers, he returned to Sydney to work for himself.

NIELSEN DESIGN ASSOCIATES

Initially he operated from home. But by 1962, the name Carl Nielsen and Associates was on the door of his first small office in North Sydney. There were other respected designers – Paul Schremmer, Ted Healy, Charles Furey – and more practitioners working within manufacturing, although Nielsen says that his was one of the first independent industrial design consultancies to operate in Sydney.

Over the next 20 years, Nielsen Design Associates (NDA) expanded into a highly-regarded multi-disciplinary design practice with graphics, interior design and model-making in addition to its industrial design and workshop capabilities. His motivation he says, was “just a burning fascination with the design business.”

“There were three key elements which affected the business of industrial design for me. One was David Wood, [who joined Nielsen in the early 1960s as an architecture student]. He had a great influence right through the office. Then there was my marvellous [second] wife, Judy Stenberg, who became our business manager. And the other thing was great clients. His father was another significant influence. “In retrospect, some of the things my father said to me had a great impact,” he says. “One was only ever work with people you can communicate with. Another was only deal with the person who’s got the authority to OK your cheques.”

MANAGING THE BUSINESS

Nielsen is emphatic that running a business in the 1960s and 70s was a much simpler task than it is today. He had no training in business management, he says, “I just ran it the way I would like to be dealt with myself.”

INVOICING – “I used to write all the fee proposals and all the invoices and I always saw them both as a key thing in relationships with clients. Invoices were sometimes three or four pages long, [and highly detailed, which] was critically important in making [clients] understand what the hell you did.”

FIRST IMPRESSIONS – “The old story is that you don’t judge a book by its cover, but you do. With clients, or potential clients, you get on with them or you don’t.” CONTROL – “It was most unusual for us to go out and do a deal in somebody else’s office because I was in their territory. It was a matter of us controlling the situation. I’ve never taken a client to lunch. I always tried to manoeuvre it so they came to our office.” THE PROFESSION – “I saw the client/designer relationship as no different to that of a doctor or lawyer. You’re a professional, and it was up to me to show them that.”

COLD CALLING – “I have never gone out and knocked on the door with a portfolio of glossy pictures because to me that sounds like being a doorto- door salesman.”

OUT AND AROUND – “I worked very hard at getting out and around. I gave lectures, so that people would ring us rather than us ring them. It was amazing how many jobs came from that.”

HIRING – “If it was the right person – how they looked and spoke, their attitude and personality – I felt you could soon teach them to do the things you wanted them to do. There’s nothing worse than having somebody brilliant at drawing or computing who’s a troublemaker or a grump.”

TIMEKEEPING – I instituted the half-hour time-book system, nothing original I’m sure, but I needed to know what was going on.

4-DAY WEEK – At David Wood’s suggestion the office adopted a 4-day week, of 9-hour days for all staff, with the proviso that client needs never be compromised and the office be open every day from 9am to 6pm.

CREATING A PROFILE

One of the early members of the Industrial Design Institute of Australia (IDIA), established in 1958, Nielsen was invited to become its second Federal President. When the Commonwealth Government founded the Industrial Design Council of Australia (IDCA), he was invited to join. In the 1960s, he did some part-time teaching on the Industrial Design Post-Graduate Diploma course at the University of NSW. And in 1974, when the NSW Government conducted an inquiry into art and design education, Nielsen was on the investigating committee. Through all of this he met a lot of people. In fact, talking to people was the strategy he used to secure business for the company. “I worked very hard at getting out and around,” he says. He’d speak at industry meetings, seminars and conferences, to the Housewives Association or The Plastics Institute, and it was “amazing how many jobs came from that, from people in the audience who came up to see me afterwards.”

CLIENTS AND PROJECTS

Some of the most well-known products designed in the NDA office in the 1960s and 70s are still around today. The company’s design for the Café Bar was innovative, effective and timely and was so successful that it became an almost ubiquitous addition to offices and factories around the country. The Optima Chair for Sebel is another example. The innovative design for this stackable upholstered chair meant that it required no specialist upholstery skills in its manufacture. It is still produced locally and under license in several countries overseas. In 1981 NDA began work for the Department of Main Roads, (now RTA) on a design for the pedestrian push button units found on traffic lights. By eliminating switching failure problems caused by water ingress and vandalism, the design has proved a lasting success. The units remain in use here and in many cities around the world.

ANALYSIS NOT ART

NDA aimed for effectiveness, functionality, economy and durability as priorities in a thorough, rational design process. “You analysed the problem, took into account the various moderating criteria and put them together in the most effective way,” says Nielsen. The styling intrinsic to many contemporary consumer products was of little interest to him. In Nielsen’s mind, there’s a very clear distinction between art and design, although he suggests that the two are so often paired these days they’ve become an entity, which he describes in a gently pejorative tone as ‘artndesign’.

“People like Philippe Stark and Marc Newson are not industrial designers in my view. They’re ‘artistsndesigners’. It’s a much more personal thing for them.” He points out that Stark, “a brilliant character,” produces primarily in Italy, where the entire gamut of design can be found, “from a sheer outrageous styling approach to the most dedicated and analysed and authoritative industrial design. “We hardly did any consumer products – that wasn’t our thing. I liked to make things that are really useful. I see no point in changing the buttons on a product to make it more saleable. You should only change it when there’s some advance to be made. And it just so happened that this strange attitude of mine coincided with the time in Australian manufacturing that happened to suit it. For many companies, the product was what it was all about.”

EDUCATING INDUSTRIAL DESIGNERS

GAP YEAR “I don’t think you should go on to advanced education straight from high school. You don’t even know who you are at age 17 or 18.”

THE RIGHT INSTITUTION

“I have a view that not everyone should go to university. There’s too much pressure to get a university education, and too many students who shouldn’t be there.” Rather than universities, Nielsen believes that the less academically oriented Colleges of Advanced Education, or the old UK-style Polytechnics were more appropriate for teaching design.

CLASS NUMBERS

In 1999 there were 25 students in Nielsen’s 4th year ID class. In 2003, the 4th year had 40 students. Next year 60 students are expected. Large class sizes, funding shortages and the sheer size of the system are the major problems design institutions face.

ACADEMIC ABILITY

After an eight-year study following HSC student entrants into industrial design, Nielsen found that “there was virtually no connection between conventional academic education and successful ID students. Some of the highest HSC students were some of the worst industrial design students and vice versa.” He found attitude, capability and life experience to be the critical ingredients.

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL DESIGNERS

When interviewing prospective industrial design students in previous years, “we thought we’d be able to choose which ones would be most successful and which wouldn’t – and a lot of the time we were right. High school applicants are no longer interviewed” but selected, by computer, on HSC scores alone.

DESIGN QUESTIONS

“My constant snap comment about students: They’re great at finding answers but they’re not so good at asking questions. Often you’ll see beautiful answers to questions nobody’s asked before.”

CHANGING TIMES

As a result of the NSW Government’s investigation into art and design education, the Gleeson Report recommended the establishment of a new College of Advanced Education. This was the Sydney College of the Arts (SCA), founded in 1976. Nielsen was asked to head up the Industrial Design Department, which he did for a year (while also running NDA), becoming Principal Lecturer on a fractional full-time, in effect, part-time, basis. “I’ve never seen myself as an academic, [but] I was getting pretty involved in education and I saw in it an opportunity to really make some change in the system.”

He pursued these two careers in tandem for some years. When the Federal Government abolished Colleges of Advanced Education – leaving only Colleges of Technical and Further Education (TAFES) and universities – the design school of SCA amalgamated with the NSW Institute of Technology. In 1988, it became the new University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), with Nielsen as Associate Professor of the Industrial Design Program within a new faculty of Design, Architecture and Building. (The art school was subsumed into the University of Sydney.)

In the 1960s and 70s, Nielsen’s clients and their factories were all within a 20 kilometre radius of the NDA office. But manufacturing began moving offshore. Companies were being bought out. “I’d say from the mid-seventies [onward], traditional manufacturing in Australia, and the people in it, seemed to change. It [became] much more impersonal. You often [had to] deal at a much lower level of the executive ladder – I took it for granted that I would always deal with the managing directors – and instead of being concerned about the product they were more concerned about shareholder returns. It’s a lot more difficult today.”

Nielsen decided to focus on teaching. He and Judy Stenberg offered the other mainstays of the office, David Wood, Sandy McNeal and Adam Laws, a buy-out proposal and in late 1984, all three became NDA’s new principals, with David Wood as Managing Director. Since that time, says Nielsen, “NDA has gone from strength to strength, sometimes along paths I would not have anticipated.”

FULL-TIME EDUCATION

In 1985 he embarked on a Master of Arts Degree, which he was awarded in 1987. As part of the course requirements, he wrote a dissertation called Industrial Design in Australia, based on an extensive questionnaire to around 380 Australian manufacturing companies. Sadly, he says, “all it did was reinforce my notion that industrial design wasn’t generally seen as a major input to industry. Even today, he says, too many companies look upon design as a cost, not an investment, whereas the design of their product is really what their business is all about.”

At both SCA and UTS, Nielsen introduced 4th year students to ‘the business’ of being an industrial designer. “I literally ran the class the way I ran the business [at NDA]. I introduced a work experience program. I used to encourage very close contact with the students and I felt my biggest input was in having discussions with them about any issue they might raise. It was never ‘chalk and talk’, it was conversation.”

He has always found teaching stimulating and satisfying, and in 1999, in acknowledgement of his ‘debt’ to the students and staff at UTS, he established The Carl Nielsen Professional Development Award – a $2,000 study/travel grant to be awarded annually to an ID graduate student. “Looking back on it,” he says, “almost everything I’ve done seems to have been connected with people and their attitudes and how I got on with them and how they got on with me.”

1930 Born and raised in Melbourne

1947 Completes high school

1949-52 Completes Industrial Design Diploma at Melbourne Technical College (now RMIT)

1953 Moves to Sydney. Makes a living as a photographer taking ‘at home’ pictures of children and families and motor racing pictures. Also furniture design and construction.

1956 Marries and begins as a design assistant at Amalgamated Wireless Australasia Ltd.

1958 The marriage ends and Nielsen leaves for London

1959-76 Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London.

1960 Back in Australia, sets up his own design business, taking on work for AWA amongst others.

1962 Carl Nielsen & Associates is the name on the door of his first small office space in North Sydney.

1963 Approached by Judy Stenberg, GM of Australian Export Promotions Ltd (AEP) to design, and supervise the installation of, an Australian trade exhibition in Manila.

1965 After several more AEP jobs, he and Stenberg marry. The consultancy moves to larger premises, staff increased. Stenberg joins the company as office manager. Nielsen elected Federal President of the recently established Industrial Design Institute of Australia (IDIA) Begins teaching part-time at UNSW’s Industrial Design Graduate Diploma course. 1971 The company incorporates under Nielsen Design Associates Pty Ltd (NDA) producing industrial, graphic, and corporate identity projects. Staff up to 17.

1972 Wanting to return to core business, they lease premises at “The Old Bakery”, Hunters Hill, where NDA still operates. Notable projects of the time include Café Bar and Sebel ‘Optima’ chairs, which are still being made.

1974 Joins a committee set up by the NSW Government to investigate design education in the state, recommending the establishment of a new College of Advanced Education.

1976 Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) established and Nielsen appointed Head of Industrial Design and Principal Lecturer.

1981 Produces pedestrian traffic-light push buttons for the Department of Main Roads (later RTA), which are still being installed today.

1984 Nielsen and Stenberg resign as directors of NDA, which continued to flourish under its new management: Sandy McNeal, Adam Laws, and David Wood, as Managing Director.

1987 Completes an MA at SCA.

1988-99 Federal Government scraps Colleges of Advanced Education. SCA amalgamates with NSW Institute of Technology which becomes the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS). Nielsen appointed Associate Professor.

1990 Founding Councillor, Australian Academy of Design.

1992 Elected Life Fellow of the Industrial Design Institute of Australia.

1999 On his departure from UTS, he establishes the Carl Nielsen Professional Development Award

2000-2003 Honorary appointment as Adjunct Professor at UTS

Originally Published in Indesign 17, May 2004

Full story HERE.